SECRET

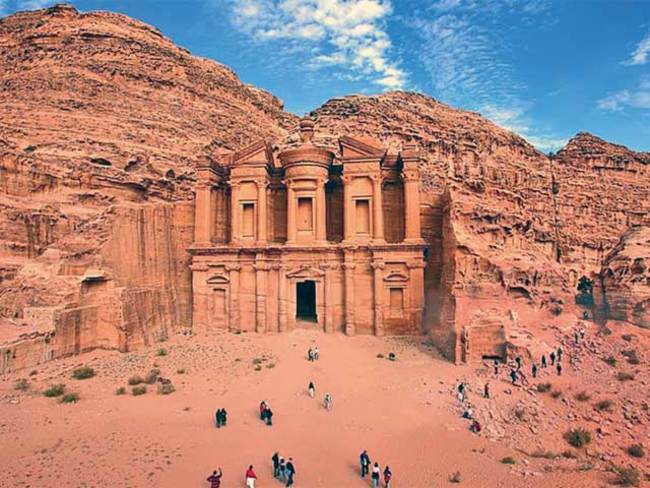

When we speak about Architectural Masterpieces, what comes to our mind? Are they monuments? Forts? Old buildings which are ruined? Almost yes. Today I am pretty much going to talk with you all about ‘Petra’. Sounds familiar right!

The famed Petra is basically an ancient city, centre of an Arab kingdom in Hellenistic and Roman times, the ruins of which are in southwest Jordan. The town was constructed on a walkway, knifed from east to west by the Wadi Mūsā —one of the dwellings where, according to tradition, the Israelite front-runner Moses hit a stalwart and water prattled forth. The gorge is bounded by stonework cliffs marked with sunglasses of red and purple varying to pastel yellow.” The modern town of Wadi Mūsā, situated contiguous to the ancient city, chiefly serves the stable stream of sightseers who continue to visit the site.

The Greek name Petra perhaps replaced the scriptural name Sela. Remains from the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods have been exposed at Petra, and Edomites are known to have engaged the area about 1200 BCE. Centuries later the Nabataeans, an Arab tribe, engaged it and made it the centre of their kingdom. In 312 BCE the region was pounce on by Seleucid forces, who failed to seize the city. During the reign of Nabataean, Petra flourished as a centre of the spice trade that involved such incongruent realms as China, Egypt, Greece, and India, and the city’s populace swelled to between 10,000 and 30,000.

Now what is interesting about Petra? The reaction to this question differs from person to person. Diggings since 1958 on behalf of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and, later, the American Centre of Oriental Research added momentously to knowledge of Petra. The ruins are usually loomed from the east by a narrow gorge known as the Siq (Wadi Al-Sīq). Among the primary sites observed from the Siq is the Khaznah, which is essentially a large ossuary. Al-Dayr is one of Petra’s remarkable rock-cut testaments; it is an uncompleted tomb facade that during Byzantine times was used as a church. Countless of the tombs of Petra have sumptuous facades and are now used as dwellings. The Great Place of Sacrifice, a cultic altar socializing from theological times, is a well-preserved site. To upkeep the ancient city’s large inhabitants, its inhabitants maintained an extensive hydrological system, including dams, cisterns, rock-carved water channels, and ceramic pipes. Excavations initiated in 1993 publicized several more sanctuaries and shrines that provide insight into the political, social, and religious traditions of the ancient city. The ruins are susceptible to floods and other natural phenomena, and amplified tourist traffic has also dented the monuments. In 1985 Petra was nominated a UNESCO World Heritage site as we all know.

Apart from all this as far as Petra is concerned at its peak, 2,000 years ago, Petra was home to as many as 30,000 people, full of temples, theatres, gardens, tombs, villas, Roman baths, and the camel caravans and souk bustle befitting the centre of an antique crossroads between east and west. After the Roman Empire invaded the city in the early second century A.D., it continued to thrive until an earthquake rattled it hard in A.D. 363. Then trade ways got rid of, and by the middle of the seventh century what persisted in Petra was largely abandoned. No one survived in it any longer except for a small tribe of Bedouins, who took up house in some of the caves and, in more recent centuries, whiled away their spare time shooting bullets into the edifices in hopes of cracking open the vaults of gold rumoured to be inside. In its retro of abandonment, the city could effortlessly have been lost incessantly to all but the tribes who lived nearby. But in 1812, a Swiss pioneer named Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, captivated by stories he’d heard about a lost city, dressed as an Arab sheikh to beguile his Bedouin guide into leading him to it. His hearsays of Petra’s remarkable sites and its whimsical caves began drawing oglers and adventurers, and they have continued coming ever since. Petra stretches and bends through the mountains, with most of its significant features collected in a flat valley. Royal catacombs line one side of the vale; religious sites line the other. A diverse, bumpy road was once Petra’s main thoroughfare; close are the ruins of a grand public cascade or “nymphaeum,” and those of several shrines, the largest of which was probably dedicated to the Nabatean sun god DuoSharp. Another, the once free-standing Great Temple—which probably served as an economic and civic centre in addition to a religious one—includes a 600-seat auditorium and a multifaceted system of subterranean aqueducts. On a small rise overlooking the Great Temple sits a Byzantine church with beautiful intact medley floors decorated with prancing, pastel animals including birds, lions, fish and bears.

After all Petra is a slice of Heaven which if unscathed harvests a mystic urge in the core of its admirers.

By Hrishikesh Goswami