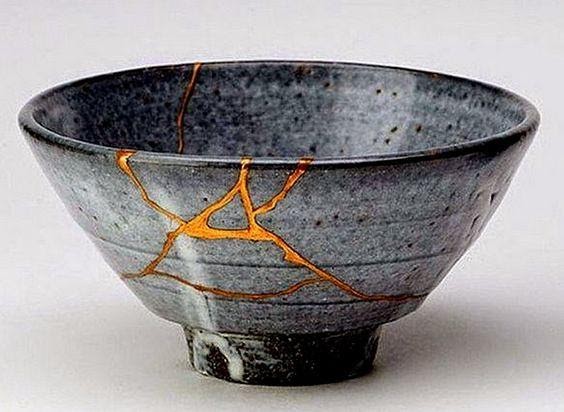

Photo credit: catherinetodd2 on VisualHunt.com

Golden lace of appreciation embraces the passing time. Celebrating the imperfections and beauty that is one-of-a-kind. In a world obsessed with perfection and symmetry, can the eyes behold the beauty of incomplete, imperfect, and impermanence of golden joinery?

A broken ceramic beauty is considered a waste, a regretful heart says its goodbyes and parts its ways. In Japan, however, the traditional art of Kintsugi teaches the world to embrace those imperfections and not consider them a waste. The broken is not meant to be hidden but displayed with great pride.

The beautiful translation of Kintsugi means ‘Golden Joinery’, or more literally translated, Kin (金) refers to gold and Tsugi (継ぎ) refers to joint. Also known as Kintsukuroi (Literally translated golden repair), the centuries-old art is a part of the Japanese philosophy Wabi-Sabi, the art of finding beauty in human flaws.

Let us set on a journey to trace the footsteps of the centuries-old Kintsugi Art, the philosophy that made it all possible, the techniques of Kintsugi, and the beautiful message behind the magnificent art.

THE DAWN OF THE GOLDEN LACE

A broken tea bowl and motivated contemporary craftsmen of Japan bought to the world one of the most meaningful art forms. Though the exact origins of Kintsugi are not clear, it is believed to be around the fifteenth century, when the 8th Shōgun of the Ashikaga shogunate, Ashikaga Yoshimasa broke his favourite tea bowl.

Sending it to China for repair, imagine Ashikaga Yoshimasa’s displeasure on finding it glued together with metal staples! The 8th shogun decided to ask Japanese craftsmen to find an alternative for its repair.

Transforming the cup with lacquered resin and powdered gold, the craftsmen not only made the repair more aesthetic but also gave birth to Kintsugi. A technique that went on to become common practice by the 17th century.

THE BEAUTY IN FLAWS: THE KINTSUGI PHILOSOPHY

Kintsugi is more than an aesthetically pleasing technique of repair. It is the pinnacle of Japanese philosophy Wabi-Sabi. The art of finding beauty in imperfections. Cherishing the passage of time – growth, change, and decay alike. The cracks and imperfections are not ugly but the symbolism of loving use. Honouring authenticity is key to the whole idea. To embrace what we have, rather than always yearning for more.

In a country that faces natural disasters frequently shunning away from nature seems acceptable. Viewing what takes from the people sometimes all that they hold dear as dangerous and disastrous. Yet, from the eyes of the people of Japan, every minuscule detail of nature – the source of all beauty – is appreciated. Not an entity to work against but to work with.

The inevitable mortality of all that exists. Nothing is complete, nothing is permanent, and nothing is perfect. It is in that impermanence, incomplete, and imperfect that true beauty is hidden.

The feeling of mottainai, a sense of regret over waste is just as pivotal in giving birth to the traditional art. In the beautiful culture of Japan, people do not shy away from conveying the feeling of awe and appreciation for what they have received. Be it from nature or other people. The spirit of mottainai is connected to this appreciation that leads to Japanese people continuing the use and repair the broken rather than replacing it with something new.

TECHNIQUES USED IN KINTSUGI

As aesthetic as the technique looks, Kintsugi is not a one-day repair project. Even today, with all the machinery at our disposal, it can still take a month to get the repair done. Interestingly, there is not just one technique used in Kintsugi. While it is common to fill the cracks with gold, silver, or platinum, mixed with lacquer of trees. Here is a look at the three different techniques:

- Crack Method: The most common Kintsugi technique, focuses on touching up the cracks with minimal lacquer and lines. The broken pieces are glued back together using the golden adhesive. The lines or “scars” become the part of the ceramic and an art in itself.

- Makienaoshi or Piece Method: When a part of the broken ceramic is beyond repair or chipped, the Makienaoshi method comes to the rescue. The missing fragments from the piece are replaced with parts made up entirely of epoxy.

- Joint-Call or Joint Method: Using potions from two different broken pieces to make a unified whole is the central idea of this method. If one is able to find pieces from different ceramics that can fit together, they have overcome the difficult part. They do not have to fit perfectly, as the Makienaoshi method can help fill the little gaps.

Varying on the technique used, the drying time can vary. On a much brighter side, with the use of ceramic adhesive, liquid gold leaf or gold mica powder, scrap paper, and thin paintbrush, anyone can start their DIY project at fixing the broken – beyond just cups, plates and vases.

Even today, both in Japan and abroad, people continue to work on Kintsugi to keep the ancient art alive and thriving.

MORE THAN WHAT MEETS THE EYE

More than the shining, shimmering gold that catches the eye, Kintsugi offers a deeper meaning to life. It teaches to accept the flaws and the scars. It reminds the beauty of human fragility and the idea of calm when something cherished is shattered. A broken object does not automatically become useless. Adorning the broken with gold, sometimes what seems like waste can become even more precious.

It is a reminder to stay optimistic when everything seems to fall apart. To celebrate the flaws, highlighting not concealing the missteps, helps become everything that is natural a part of the piece as well.

Kintsugi holds the essence of resilience in its finest details. The ability to adapt in the face of crisis. Just like the precious ceramic that slips from between one’s fingertips, our world may seem to come crashing down. Instead of considering it all a waste, a more positive outlook, learning from the negative experience makes the return to the pre-crisis self more likely.

Of course, the damages cannot be fully repaired, the cracks would show. But it is exactly these cracks and experiences that make every individual unique and their beauty shine from within. Just like the Kintsugi is made from the different way each piece shatters, turning it precious by embracing the “scars”. We, too, are made up of our wounds. Each telling their own stories, filling us with unimaginable beauty, leaving a different mark.

Author Bio: Disha Walia is a writer, editor for those who have trouble putting thoughts into words, and a lifelong storyteller. As a Psychology graduate with a Master’s degree in English, she loves exploring the unknown world of words with an interdisciplinary approach. She has a love for hobbies that focus on finer details, creativity, and intriguing depths.